Independence threatened as public defenders strive for parity in King County, Washington

Pleading the Sixth: In 2011, the Washington State Supreme Court affirmed a lower court ruling that employees of the four independent, non-profit public defense organizations in King County (Seattle) must be considered as county employees for the purposes of participation in the public employee retirement fund. As a settlement in the case looms, King County announced in November 2012 its intent to stop contracting with the public defender agencies and create a new county-employee public defender office. Will the push for “parity” result in a loss of independence for a right to counsel system that is regarded nationally as one of the best?

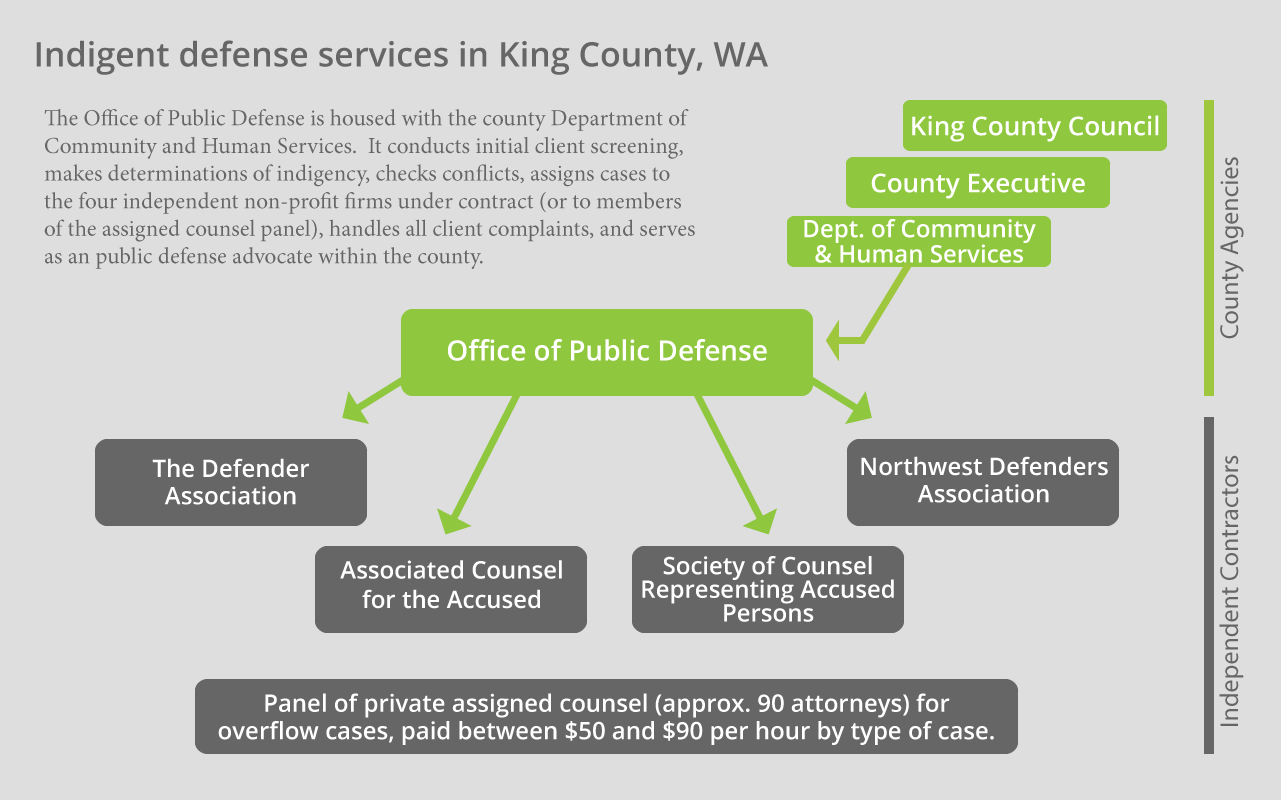

On November 29, 2012, the Seattle Times reported that King County executive is proposing to stop contracting with the four, independent non-profit organizations that provide right to counsel services when their current contracts expire on June 30, 2013, and, instead, create a county-employee public defender system. (For an explanation of how King County’s current indigent defense system is structured, see image below.)

The proposed change is the direct result of a looming settlement in a class action suit in which the Washington Supreme Court affirmed a lower court’s determination that employees of the public defender agencies should be considered county employees for purposes of participating in the public employee retirement fund. Critics of the announced plan charge that a move to make public defenders county employees will undercut the independence built into the system’s current structure. This independence, after all, is what has made the King County indigent defense system a model for the rest of the country.

Dolan v King County

The American Bar Association, Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System Principle 8 requires “parity between defense counsel and the prosecution” with respect to salaries, workload, access to investigators and experts, and an equal voice in criminal justice policy, among others. Though the King County indigent defense system meets the vast majority of the ABA Ten Principles, the mandate for parity has historically not been met.

For example, in 1989 King County retained the services of a consulting firm to study the issue of pay parity between the defense and prosecution functions. And, though the county agreed to a plan to implement pay parity over a three-year period, salary parity was never achieved. In reaching its 2011 decision in Dolan v. King County, the state Supreme Court examined the local changes resulting from the 1989 parity study and found that “the county failed to provide funding for senior defender positions and therefore the organizations had to classify defenders in lower classifications than prosecutors with similar experience.” In addition, the “county also took the position that parity only applied to base pay and not benefits.” Specifically,they “did not provide sufficient funding for the defender organizations to make meaningful retirement contributions.” There is little doubt that King County had not reached parity in any meaningful way.

Dolan v. King County alleges that, despite the existence of four non-profit entities, over time the county had exerted more and more influence over the agencies to the point where the agencies were independent in name only. For example, in the mid-1980s, the county desired for there to be a public defender agency that had a staff composed predominantly of racial minorities. In response to the county’s wishes, the Northwest Defenders Association (NDA) was established in 1987. In 2002, NDA went into receivership and as a result “the county required changes in the composition of the board of directors, bylaws, corporate articles, employee policies, financial practices, and contract with the county for all of its public defender organizations.” As a result of the contracting changes, the county was given the authority to “terminate the contract without cause,” “review client files,” and to restrict all public defender organizations’ “ability to turn down individual cases.” These changes, taken together with a budgeting process that mirrored all other county departments’ budgeting process, made the four agencies, in the minds of the plaintiffs, de facto county employees entitled to equal pay and benefits.

The county took a different view, arguing that because “defenders are free to defend clients without interference and may hire and fire without interference,” they are not akin to county employees. However, the Washington Supreme Court disagreed. “Under its reasoning, the county could turn its sheriff’s department into a nonprofit corporation and because the sheriff generally has authority to hire and fire and carry out police work, the sheriff’s department would become an independent contractor. The county is wrong.”

The King County Proposal & Response

Though terms of the settlement are not yet public, there is a presumption that King County is facing a large payout. And, to guard against future lawsuits and potential damages the county now aims to end the current King County indigent defense system and make all public defender county employees starting on July 1, 2013. Beyond those basic parameters, no one knows the details of what the county is planning or how changes will be implemented. This vacuum of information has led to much speculation.

On December 3, 2012, the Seattle Weekly published an interview with the named plaintiff, Kevin Dolan. He applauds the move to county employment and suggests that the county can keep the existing agency structure and “designate them as department or sub-groups” within a single umbrella defense agency. In essence, he would elevate the head of the Office of Public Defense to be the King County Public Defender.

The heads of the four non-profit agencies see the situation differently. In a joint December 5, 2012 letter to the King County Council, the defender organizations argue that the Dolan decision does not require the county to make public defenders county employees, but simply “that it must pay equivalent benefits regardless of how public defense is structured.” The defenders point to Public Defender Services for the District of Columbia – another of our country’s best indigent defense systems – as an example of a public defender program that is independently directed and whose employees are explicitly not federal employees, yet who receive federal benefits as if they were federal employees. As members of the plaintiff class, the four agency heads state that they will ask their lawyers “not to agree to any settlement that would effectively end our nationally recognized independent public defense system.” They also requested that the King County refrain from approving any settlement that “conditions fair benefits for our staff on those staff working directly for King County.”

The fear of changing to an in-house system is based on a myriad of concerns. For example, as non-profit entities the public defender organizations can seek philanthropic dollars to support innovative projects, which an official government agency would be precluded from doing. The Defender Association (TDA) uses non-county funding to engage in innovative endeavors, including: serving as the Washington Death Penalty Assistance Center – a training and consultation center assisting attorneys in death-eligible cases across the state; and, the Racial Disparity Project – a legal advocacy and public education resource seeking to reduce racial bias in the criminal justice system. TDA also developed and launched TeamChild – a separate non-profit organization designed to help at-risk youth with legal advocacy and advice to help them, for example, “get back in school, find safe and stable housing, get healthcare and mental health services, and access other public support.” Like TDA, The Society of Counsel Representing Accused Persons (SCRAP) uses its non-profit status to support innovative programs to address the disproportionate representation of youth of color in the juvenile justice system and to provide legal advocacy to children trying to obtain legal immigration status.

King County public defenders have been at the forefront of challenges to improve the fairness of the criminal justice system and fear that mission will be lost as county employees. In the October 2012 issue of the King County Bar Association’s Bar Bulletin, Seattle University Law Professor John Strait notes that the King County public defenders have “helped streamline contempt of court proceedings in child support enforcement cases,” and “helped design re-licensing programs so clients can negotiate the often confusing process of regaining their driver’s license” among other reforms that significantly reduce “the number of charges filed by the prosecutor while improving public safety.” King County defenders also led the charge to adoption of binding caseload standards by the Washington Supreme Court, as noted in a July 2012 Seattle Timesopinion piece by the former head of The Defender Association, Robert Boruchowitz.

King County has been down this road before

As stakeholders on all sides of the issue await the settlement and a detailed county plan, it is important to note that this is not the first time that the issue of making public defenders county employees has been raised in King County. In 2000, The Spangenberg Group (TSG) released its King County Public Defense Study that examined alternative models for delivering Sixth Amendment services, including making public defenders county employees. (The author of this blog post was an employee of the Spangenberg Group at the time of the report.)

The TSG report does a good job of detailing the pros and cons of such a move. On the plus side, making public defenders county employees would result in: a “reduction in administrative staff, and thus reduced administrative costs due to centralization of services and economies of scale;” coordinated management information and case-tracking systems; and “a more consistent and credible level of oversight and evaluation of the public defender system.” And, finally, public defenders and support staff would get better salaries and benefits.

On the negative side of the equation, TSG saw many potential hazards. For example, there would be a significant number of conflicts caused if the staffs of the four agencies were merged into one primary and one conflict office. This would lead to an expansion of a reliance on private bar attorneys billing hourly, and would most likely cause an increase in county costs. TSG also determined that there would be “certain costs” involving “the winding-up of two or more agencies, including such things as buy-out of leases, disposal of equipment, pay-off of accrued vacation and health benefits and other union issues that might be affected.”

Presented to a King County criminal justice task force composed of judges, prosecutors defenders, and county administrative officials, among others, it was determined that “the potential positive results are far outweighed by the substantial additional costs and other disrupted factors.” And so the system of contracting with the four independent non-profit law firms for public defense services was left in place.

Conclusion

In the commentary to ABA Principle 1 requiring the independence of the defense function, the ABA notes that in addition to public defenders being “subject to judicial supervision only in the same manner and to the same extent as retained counsel” the public defense function should also “be independent from political influence” as well. ABA Principle 1 commentary specifically recommends to “safeguard independence and to promote the efficiency and quality of services, a nonpartisan board should oversee defender, assigned counsel, or contract systems.

The TSG report suggested something similar, with the Office of Public Defense being taken out of the Department of Community and Human Services and put under an independent commission. Whether such a move would allay some of the fears of those predicting a loss of independence is still to be seen. Additionally, until a detailed county plan is made public, no one knows if such a commission is even envisioned by the county. The Sixth Amendment Center urges King County officials to move cautiously, be transparent in planning process and be inclusive in getting feedback from defenders and the broader community.

We will keep you posted as things progress.