US DOJ enters Statement of Interest in NYCLU class action lawsuit

Pleading the Sixth: The U.S. Department of Justice entered a Statement of Interest in a class action lawsuit brought by the New York Civil Liberties Union alleging egregious Sixth Amendment violations in that state. Importantly, the Statement denotes DOJ’s position on the systemic deficiencies that result in constructive denial of counsel, including “severe lack of resources,” “unreasonably high caseloads,” and a lack of “appropriate investigations.” Will this action prove to be the game changer needed to remedy New York and America’s indigent defense crises? The 6AC says “yes.”

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has stated on numerous occasions that right to counsel services in America “exist in a state of crisis.” The method through which the indigent accused is provided the constitutional right to an attorney is described alternatively in DOJ speeches as, “inadequate,” “broken,” and “unjust,” with “devastating” consequences to both the defendant and to society as a whole. The situation is “unacceptable,” “unconscionable” “morally untenable,” “economically unsustainable,” and “unworthy of a legal system that stands as an example to all the world.” Never content to simply talk about the crisis, on September 25, 2014, the DOJ actively set about remedying the longstanding, deep-rooted right to counsel deficiencies that plague our nation’s state courts by filing a Statement of Interest in the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) Sixth Amendment class action lawsuit, Hurrell-Harring.

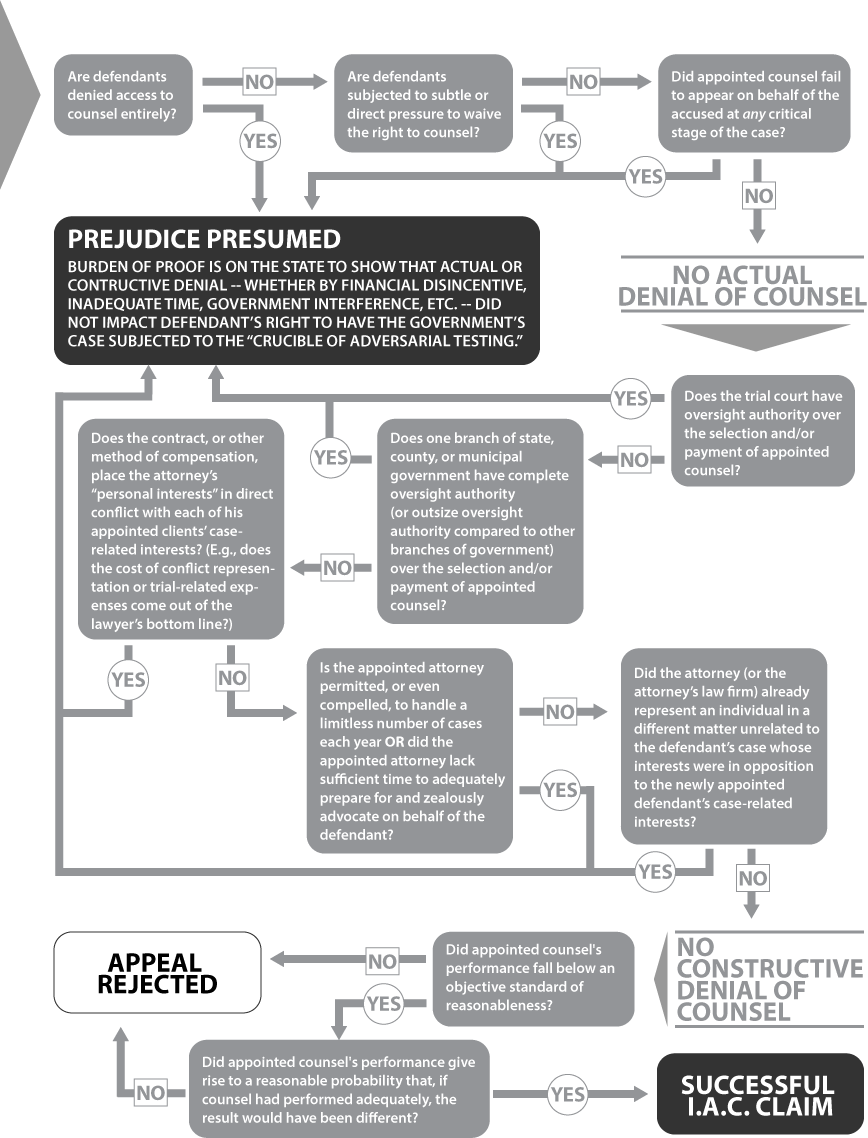

The NYCLU complaint alleges a systemic denial of counsel in five upstate New York counties. Similar to the DOJ Statement of Interest entered in Wilbur v. Mount Vernon, the new DOJ court filing does not take a position on the merits of the NYCLU’s claims. Rather, the DOJ offers its expertise to the Court on what constitutes a “constructive” denial of counsel under the Sixth Amendment. As opposed to an “actual” denial of counsel that occurs when no attorney is present at a critical stage of a criminal or delinquency proceeding, a “constructive” denial of counsel occurs when certain systemic impediments exists such that defendants receive what amounts to no representation at all, despite the physical presence of a defense attorney.

In short, the DOJ statement establishes that a court does not have to wait for a case to be disposed of to begin trying to unravel retrospectively whether a specific defendant’s representation met the aims of Gideon v. Wainwright and the Sixth Amendment. If state or local governments create structural impediments that make the appointment of counsel “superficial” to the point of “non-representation,” a court can step in and presume prospectively that the representation is ineffective. The types of government interference enunciated in the DOJ Statement of Interest include (but most assuredly are not limited to): “a severe lack of resources,” “unreasonably high caseloads,” “critical understaffing of public defender offices,” and/or anything else making the “traditional markers of representation” go unmet (i.e., “timely and confidential consultation with clients,” “appropriate investigations,” and adversarial representation, among others).

The Impact on New York

Though the DOJ did not weigh in on the merits of the NYCLU’s allegations, there is little doubt that the indigent accused experience both actual and constructive denial of counsel on a daily basis in the various criminal and delinquency courts throughout New York.

New York delegates to its counties the responsibility for administering the provision of right to counsel services at the trial level, along with the majority of the state’s obligation for funding of those services. As a result, there is no consistency from one county to the next in the method employed, nor in the consistency of funding provided across the state.

Perhaps in an attempt to make the allegations in Hurrell-Harring mute, in 2010 the New York legislature created the Office of Indigent Legal Services (ILS). ILS is a state agency of the executive branch, overseen by a nine-member board, with limited authority to assist the state’s county-based indigent defense systems to improve the quality of services provided. It does so primarily through funding assistance grants to counties.

However, a new report by ILS, released the day before the DOJ filing, shows that the office is having only marginal impact in regard to lowering excessive caseloads throughout the upstate counties. ILS estimates that $105,199,248 additional dollars are needed in New York to have caseloads meet national workload standards that, the American Bar Association (ABA) Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System (Principle 5) states, “should in no event be exceeded.” To meet those standards, New York would need to add 530 new attorneys and 294 support staff in those upstate New York counties using institutional providers to lower the number of new cases assigned from the current high of 680 new assignments (an average blended caseload of felony, misdemeanor, delinquency, and family cases) to the goal of having each attorney being assigned only 367 new cases per year (or more than one new case every single day of the year, including weekends and holidays).

However, ILS is not alone in exposing the structural inefficiencies of the right to counsel in New York. Other major reports published just since the turn of the millennium include:

- NYCLU. State of Injustice: How New York State Turns its Back on the Right to Counsel for the Poor. September 17, 2014. (“Experts were consulted in effectively zero percent of the tens of thousands of public defense cases in Suffolk County. . . . In Onondaga, Suffolk and Schuyler counties, criminal defendants regularly appeared at arraignment without attorneys.”)

- National Legal Aid & Defender Association. Justice Impaired: The Impact of the State of New York’s Failure to Effectively Implement the Right to Counsel. October 2007. (“Defendants unable to afford counsel and facing felony charges could expect public defenders to spend an average of just 3.9 hours on their case – whether it is a bad check charge or a complex homicide – compared to the nationally recognized standard of 13.6 hours per case. More time spent on any one case means less time spent on others.”)

- Commission on the Future of Indigent Defense Services. Final Report to the Chief Judge of the State of New York. June 2006. (“New York’s current fragmented system of county-operated and largely county-financed indigent defense services fails to satisfy the state’s constitutional and statutory obligations to protect the rights of the indigent accused.”)

- The Spangenberg Group. Status of Indigent Defense in New York: A Study for Chief Judge Kaye’s Commission on the Future of Indigent Defense Services. June 2006. (“New York’s indigent defense system is in a serious state of crisis.”)

- New York State Bar Association, Special Committee to Ensure Quality Mandated Representation. Standards for Providing Mandated Representation. April 2005. (“It is vital that funding sources provide funding adequate to enable providers to meet or exceed the requirements of these standards.”)

If the NYCLU allegations are found to be true, the DOJ Statement of Interest notes that it is entirely appropriate for the court to appoint a monitor to help remedy the situation. Citing back to its statement in the Wilbur case out of Washington state, the DOJ noted that in addition to overseeing appropriate workload, a “monitor can also assess whether, regardless of workload, defenders are carrying out other hallmarks of minimally effective representation, such as visiting clients, conducting investigations, performing legal research, and pursuing discovery . . . These kinds of detailed inquiries, carried out over sufficient time to ensure meaningful and long-lasting reform, are critical to assessing whether [jurisdictions] are truly honoring misdemeanor defendants’ right to counsel, and they can be made most efficiently and reliably by an independent monitor.”

The National Impact

Though poor people accused of crime in New York stand to benefit directly form the DOJ intervention, the 6AC believes the new DOJ filing will be a game changer on the national front too. Since the systemic parameters needed to foster effective representation espoused in the DOJ Statement closely mirror the majority of the ABA Ten Principles, the DOJ action may prove to be the key to establishing the Principles as the minimum structural threshold envisioned in United States v. Cronic that must be prospectively met before an individual case can proceed to disposition and then be reviewed retrospectively for ineffective assistance of counsel under Strickland v. Washington. Let us explain.

Though numerous critics have bemoaned Strickland’s seemingly high threshold for establishing the ineffectiveness of a particular defense attorney’s representation, we ask the reader to take the position for the moment that Strickland sets out a reasonable approach for judging the effectiveness of an individual lawyer’s representation in an specific case. At least it may be reasonable if the lawyer being judged works in a functioning indigent defense system.

It is the position of the 6AC that, since Cronic and Strickland were heard and decided on the same day, the two landmark cases are intended to be read on a continuum whereby each successive criterion must be satisfied before moving on to the next. Strickland’s two-prong criterion, whereby a defendant seeking to overturn a conviction based on the ineffectiveness of their court-appointed lawyer must prove that the appointed lawyer’s actions were unreasonable and prejudiced the outcome of the case exists, resides at the very far end of the spectrum.

At the initial end of the continuum resides Cronic. If certain systemic factors exist at the outset of the case, then a court should presume that ineffective assistance of counsel will occur. The first factor that triggers that presumption is the absence of counsel to the accused at any of the “critical stages” of a case, as defined by the U.S. Supreme Court. This would include the actual denial of counsel resulting from the type of indeterminate representation detailed in our blog piece on the failure to appointed counsel early enough in the proceeding in Scott County, Mississippi.

Cronic, however, then goes on to explain that there are systemic deficiencies that would make any lawyer, even the best attorney, perform in a non-adversarial way. Though the Court has never presumed that the list of systemic impediments is capped, they clearly advise that the types of systemic deficiencies they are talking about include: a) governmental interference with counsel assistance; and/or, b) the creation of actual conflicts of interest for the lawyer.

The new DOJ Statement of Interest basically clarifies this section of Cronic for all future court actions. For example, Cronic points to the deficient representation received by the so-called “Scottsboro Boys,” and detailed in Powell v. Alabama, as demonstrative of the type of constructive denial of counsel that violates the Sixth Amendment. Powell notes that one of the primary reason for the Scottsboro Boys’ constructive denial of counsel is the lack of “sufficient time” to advise with counsel and to prepare an adequate defense, commenting that impeding counsel’s time “is not to proceed promptly in the calm spirit of regulated justice, but to go forward with the haste of the mob.” ABA Principle 4 likewise requires indigent defense systems to provide public defense lawyers with sufficient time, and the DOJ Statement of Interest similarly denotes that the lack of time to fulfill “lawyers basic obligations to their client” is a hallmark of constructive denial of counsel.

With sufficiency of time being the key to determining a constructive denial of counsel, one can align most of the other ABA Ten Principles and come to an understanding that failure meet the Principles result in an infringement on the time necessary to fulfill the basic parameters of effective representation, including: having excessive caseloads (Principle 5); engaging in non-continuous representation by the same attorney (Principle 7); appointing lawyers far too late in the life of a case (Principle 3); or contracting with attorneys under a flat fee arrangement that gives fiscal incentives or disincentives to lawyers for disposing of cases quickly (Principle 8). Frequent readers of this blog will also recognize that this author’s experience dictates that all issues related to a lack of sufficient can be boiled down to a lack of independence of the defense function (Principle 1).

So what the DOJ Statement of Interest is really saying is that since the majority of state and county indigent defense systems in this country are systemically deficient, Strickland should be restricted to only the very few jurisdictions with public defender offices and coordinated assigned counsel systems are structurally sound (i.e., that meet the majority of the ABA Ten Principles). Or, more directly, it is making clear that it is unconstitutional, under Gideon and its progeny, for a state to allow the operation of structurally deficient indigent defense services – whether through ignorance, willful neglect or malice – that structurally interfere with the independence of the lawyers practicing in the indigent defense system to zealously advocate in the stated interests of the indigent accused.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that the new DOJ Statement of Interest will have impact across the country as states, like Idaho and Mississippi, are already contemplating indigent defense reforms based on actual litigation or the mere threat of litigation. As the DOJ states, the “United States has an interest in ensuring that all jurisdictions – federal, state, and local – are fulfilling their obligation under the Constitution to provide effective assistance of counsel to individuals facing criminal charges who cannot afford an attorneys, as required by Gideon.” Their actions in Shelby County, Tennessee, and their investigations in St. Louis, Missouri, should put states on notice that the failure to meet Gideon is no longer being tolerated.

But the real hope is that the new DOJ Statement of Interest will put to rest all the arguments heard in numerous jurisdictions across the country that the lack of successful ineffective assistance of counsel claims under Strickland is somehow proof that no right to counsel crisis exists. Our state and federal appellate court systems are simply unable to retroactively fix these long-standing, deep-rooted deficiencies in the provision of right to counsel services on a case-by-case basis. For instance, upwards of 90% of all criminal cases are resolved nationally through plea bargains, not trials (oftentimes because of actual or constructive denial of counsel). The circumstances in which those 90% of cases disposed of by plea can be appealed are so rare as to make their number inconsequential. And, only a tiny fraction of those remaining 10% of cases disposed through trial ever move on to the appellate system. But even then, the most deficient indigent defense services in America require the same attorney who represents the defendant at trial to also handle the direct appeal. What are the chances of an overworked, unprepared, financially conflicted public defense attorney ever raising ineffective assistance of counsel claims against themselves in a direct appeal?

Since the Strickland argument often arises from district attorneys, we hope prosecutors heed the words of the DOJ (quoting the ABA Criminal Justice Standards, Standard 3-1.2): “It is an important function of a prosecutor to seek reform and improve the administration of justice. When inadequacies or injustices in the substantive or procedural law come to the prosecutor’s attention, he or she should stimulate efforts for remedial action.” We invite prosecutors across the country to partner with advocates in fixing our national right to counsel crisis.