A Cronic resolve to America’s chronic right to counsel deficiencies

Pleading the Sixth: On September 28, 2016, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that indigent defendants have a right to challenge systemic deficiencies at the outset of a case before having to suffer from actual or constructive denial of counsel. (Click here for a companion piece on that ruling.) But how does one assess the systemic denial of counsel? Here, the 6AC explains how we evaluate right to counsel systems using United States v. Cronic.

It is not enough for states to merely provide what some have referred to as a warm body with a bar card to stand beside an indigent person. Instead, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that the lawyer provided to represent an indigent person must also be effective.

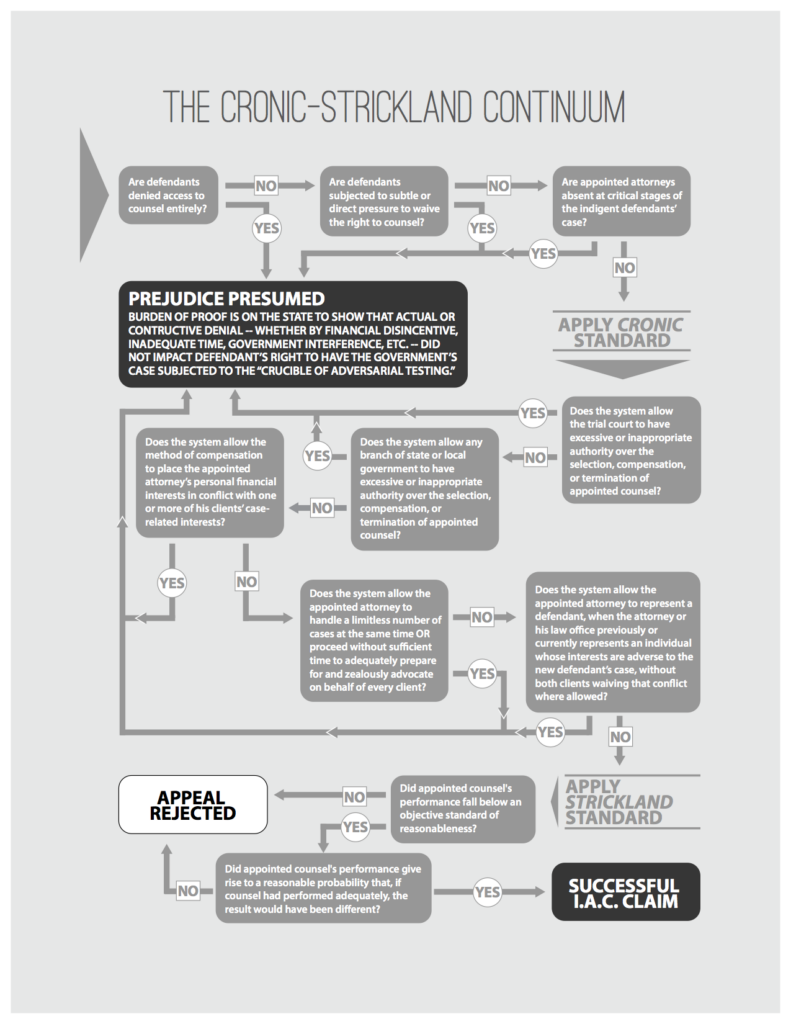

Two principal U.S. Supreme Court cases, decided on the same day, describe the tests employed to determine the constitutional effectiveness of right to counsel services. United States v. Cronic and Strickland v. Washington together describe a continuum of representation. Strickland is backward-looking and it is used after a case is final to decide whether the lawyer provided effective assistance of counsel in a particular case, setting out a two-pronged test that asks whether the appointed lawyer’s actions were unreasonable and prejudiced the outcome of the case. Cronic is forward-looking and states that, if certain systemic factors are present (or necessary factors are absent) at the outset of a case, then a court should presume that ineffective assistance of counsel will occur. Hallmarks of a structurally sound indigent defense system under Cronic include the early appointment of qualified and trained attorneys with sufficient time and resources to provide competent representation under independent supervision. The absence of any of these factors can show that a system is presumptively providing ineffective assistance of counsel.

Presence of counsel at critical stages. The first factor that triggers a presumption of ineffectiveness is the absence of counsel for the accused at the “critical stages” of a case. Arraignments, plea negotiations, and sentencing hearings, for example, are all critical stages of a case. (For a full discussion of all the “critical stages” of a case, see the 6AC report Early Appointment of Counsel: The Law, Implementation and Benefits.) If counsel is not present at every one of these critical stages, an actual denial of counsel occurs. (Read about the prevalence of actual denial of counsel in the 6AC report Actual Denial of Counsel in Misdemeanor Courts.)

Attorney qualifications, training, and resources. Next, the U.S. Supreme Court explains in Cronic that there are systemic deficiencies that make any lawyer – even the best attorney – perform in a non-adversarial way. As opposed to the “actual” denial of counsel of Cronic’s first prong, the Court calls this a “constructive” denial of counsel. The overarching principle in Cronic is that the process must be a “fair fight.” Cronic notes that the “fair fight” standard does not necessitate one-for-one parity between the prosecution and the defense. Rather, the adversarial process requires states to ensure that both functions have the resources they need at a level their respective roles demand. As the U.S. Supreme Court notes: “While a criminal trial is not a game in which the participants are expected to enter the ring with a near match in skills, neither is it a sacrifice of unarmed prisoners to gladiators.”

Cronic’s necessity of a fair fight requires that the defense attorney put the prosecution’s case to the “crucible of meaningful adversarial testing.” If a defense attorney is either incapable of challenging the state’s case or barred from doing so because of a structural impediment, a constructive denial of counsel occurs. In Cronic, the Court points to the deficient representation received by the defendants known as the “Scottsboro Boys,” and detailed in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Powell v. Alabama, as demonstrating constructive denial of counsel. The trial judge overseeing the Scottsboro Boys’ case appointed a real estate lawyer from Chattanooga, who was not licensed in Alabama and was admittedly unfamiliar with the state’s rules of criminal procedure. The Powell Court concluded that defendants require the “guiding hand” of counsel – i.e., attorneys must be qualified and trained to help the defendants advocate for their stated interests.

Sufficient time. Having been assigned unqualified counsel, the Scottsboro Boys’ trials proceeded immediately that same day. Powell notes that the lack of “sufficient time” to consult with counsel and to prepare an adequate defense was one of the primary reasons for finding that the Scottsboro Boys were constructively denied counsel, commenting that impeding counsel’s time “is not to proceed promptly in the calm spirit of regulated justice, but to go forward with the haste of the mob.” Insufficient time is, therefore, a marker of constructive denial of counsel, and the inadequate time may itself be caused by any number of things, including but not limited to excessive workloads or contractual arrangements that create monetary incentives for lawyers to dispose of cases as quickly as possible rather than in the manner most effective for defendants.

Independence of the defense function. Perhaps the most noted critique of the Scottsboro Boys’ defense was that it lacked independence from governmental interference, specifically from the judge presiding over the case. As noted in Strickland, “independence of counsel” is “constitutionally protected,” and “[g]overnment violates the right to effective assistance when it interferes in certain ways with the ability of counsel to make independent decisions about how to conduct the defense.” In specific relation to judicial interference, the Powell Court stated:

[H]ow can a judge, whose functions are purely judicial, effectively discharge the obligations of counsel for the accused? He can and should see to it that, in the proceedings before the court, the accused shall be dealt with justly and fairly. He cannot investigate the facts, advise and direct the defense, or participate in those necessary conferences between counsel and accused which sometimes partake of the inviolable character of the confessional.

In other words, it is never possible for a judge presiding over a case to properly assess the quality of a defense lawyer’s representation, because the judge can never, for example, read the case file, question the defendant as to his stated interests, follow the attorney to the crime scene, or sit in on witness interviews. That is not to say a judge cannot provide sound feedback on an attorney’s in-court performance – the appropriate defender supervisors indeed should actively seek to learn a judge’s opinion on attorney performance. And, in some extreme circumstances, a judge can determine that counsel is ineffective, for example, if the lawyer is sleeping through the proceedings. It is just that the judge’s in-court observations of a defense attorney cannot comprise the totality of supervision.

While Cronic and Powell focus on independence of counsel from judicial interference, other U.S. Supreme Court decisions extend the independence standard to political interference as well. In the 1979 case of Ferri v. Ackerman, the United States Supreme Court stated that “independence” of appointed counsel to act as an adversary is an “indispensible element” of “effective representation.” Two years later, the Court observed in Polk County v. Dodson that states have a “constitutional obligation to respect the professional independence of the public defenders whom it engages.” Commenting that “a defense lawyer best serves the public not by acting on the State’s behalf or in concert with it, but rather by advancing the undivided interests of the client,” the Court notes in Polk County that a “public defender is not amenable to administrative direction in the same sense as other state employees.” The Cronic Court clearly advises that governmental interference that infringes on a lawyer’s independence to act in the stated interests of defendants or places the lawyer in a conflict of interest causes a constructive denial of counsel.

Cronic determined that, when a public lawyer works within a system where factors are present that constructively deny the right to counsel, then the public lawyer is presumptively ineffective. The government bears the burden of overcoming that presumption. The government may argue that, despite such conflicts, the defense lawyer in a specific case was not ineffective, but it is the government’s burden to establish this. As the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals noted in Wahlberg v. Israel, “if the state is not a passive spectator of an inept defense, but a cause of the inept defense, the burden of showing prejudice [under Strickland] is lifted. It is not right that the state should be able to say, ‘sure we impeded your defense – now prove it made a difference.’” Only after the system within which public attorneys work is found to be structurally sound, as defined and prospectively determined by a Cronic and Powell analysis, can Strickland’s two-prong test be used to retrospectively measure the effectiveness of specific attorneys who work within those structurally sound indigent defense systems.

The U.S. Department of Justice urges this same application of Cronic

On September 25, 2014, the DOJ filed a Statement of Interest in a class action lawsuit, Hurrell-Harring v. New York, brought by the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) alleging a systemic denial of counsel in five upstate New York counties. (For the latest impact of Hurell-Harring lawsuit, click here and here.) The Statement of Interest provides DOJ’s expertise to the court on what constitutes a “constructive” denial of counsel under the Sixth Amendment. In short, the DOJ statement establishes that a court does not have to wait for a case to be disposed of and then try to unravel retrospectively whether a specific defendant’s representation met the aims of Gideon and its prodigy. If state or local governments create structural impediments that make the appointment of counsel “superficial” to the point of “non-representation,” a court can step in and presume prospectively that the representation is ineffective. The types of government interference enunciated in the DOJ Statement of Interest include (but most assuredly are not limited to): “a severe lack of resources,” “unreasonably high caseloads,” “critical understaffing of public defender offices,” and/or anything else making the “traditional markers of representation” go unmet (i.e., “timely and confidential consultation with clients,” “appropriate investigations,” and adversarial representation, among others).

In another Statement of Interest filed August 14, 2013, in Wilbur v. City of Mount Vernon, the DOJ comments specifically on the issue of public defense attorneys having sufficient time to provide adequate representation. At the heart of the Wilbur case was the issue of how excessive caseloads of public defense attorneys resulted in deficient representation under the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. At the time the original complaint was filed in 2011, the cities of Mt. Vernon and Burlington, Washington, jointly contracted with two private attorneys to represent indigent defendants in their municipal courts, as they had done “for nearly a decade.” Under the contract, the two attorneys served together as “the public defender” and were paid a flat annual fee out of which they had to provide all “investigative, paralegal, and clerical services” without any additional compensation. In other words, the more work and non-attorney support they dedicated to their clients’ cases, the less each attorney’s take-home pay. And each contracting attorney handled between 950 and 1,150 appointed cases each year, in addition to maintaining a healthy private practice on the side. With such heavy caseloads, the contract defenders were alleged to “regularly fail to return calls” or “meet with” or “interview” their clients, and “rarely, if ever, investigate the charges made against” their clients. And the cities’ failure to adequately “monitor and oversee” the system they operated by way of the contract amounted to a “construct[ive] denial of the right to counsel” as guaranteed under Gideon. (Read here about how a U.S. District Court found the two Washington cities are responsible for the systemic deficiencies depriving the indigent accused of their constitutional right to meaningful representation.)

Pointing to the ABA’s Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System, the DOJ urged the court to consider that every jurisdiction should have caseload controls, but that caseload limits alone cannot keep public defenders from being overworked into ineffectiveness; two additional protections are required. First, a public defender must have the authority to decline appointments over the caseload limit. Second, caseload limits are no replacement of a careful analysis of a public defender’s workload, a concept that takes into account all of the factors affecting a public defender’s ability to adequately represent clients, such as the complexity of cases on a defender’s docket, the defender’s skill and experience, the support services available to the defender, and the defender’s other duties.

The DOJ has twice filed amicus briefs furthering their position on constructive denial of counsel. Most recently, on May 12, 2016, DOJ filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court of Idaho in Tucker v. Idaho, in which the ACLU of Idaho alleges systemic denial of counsel for the indigent accused. As in Hurrell-Harring, the DOJ states in Tucker that a “constructive denial of counsel violating Gideon occurs where the traditional markers of representation are frequently absent or significantly compromised as a result of systemic, structural limitations.”

On September 11, 2015, the DOJ filed an amicus brief in Kuren v. Luzerne County at the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The Kuren class action lawsuit alleged that the county so poorly funded right to counsel services as to constructively deny counsel to the indigent accused. The DOJ amicus brief makes clear that a civil constructive denial of counsel claim is an “effective way for litigants to seek to effectuate the promise of Gideon,” and “[p]ost-conviction claims cannot provide systemic structural relief that will help fix the problem of under-funded and under-resourced public defenders.” (Click here for our companion piece on a recent ruling in the case.)

The DOJ has also made clear that its Cronic analysis applies equally to juvenile delinquency proceedings, through its Statement of Interest in N.P. v. Georgia, filed March 13, 2015. The Southern Center for Human Rights (“SCHR”) filed the class action lawsuit alleging that children were regularly denied their right to counsel and instead treated to “assembly-line justice” in the Cordele Judicial Circuit. According to SCHR, kids regularly appeared in court without lawyers, and those who did receive representation were assigned lawyers who did not have time to talk with them before court. The suit claimed that the Cordele Circuit Public Defender Office was structurally unable to provide meaningful representation due to chronic underfunding and understaffing. The DOJ Statement provides the trial court with a Cronic framework to evaluate the claims. (Read about the consent decree in the case here.)

Finally, the DOJ has taken action to enforce the four main principles enumerated in Cronic. On April 26, 2012, the DOJ Civil Rights Division delivered a report, Investigation of the Shelby County Juvenile Court, to officials in Shelby County (Memphis), Tennessee, stating that the juvenile court of Memphis and Shelby County (JCMSC) “fails to ensure due process for all children appearing for delinquency proceedings” in direct violation of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in In re Gault. An agreement was reached requiring the county and JCMSC to ensure, among other things, that “juvenile defenders have appropriate administrative support, reasonable workloads, and sufficient resources to provide independent, ethical, and zealous representation to children in delinquency matters” at “all stages of the juvenile delinquency case, including pre-adjudicatory investigation, litigation, dispositional advocacy, and post-dispositional advocacy,” for as long as a case is active. The agreement additionally requires “the promulgation and adoption of attorney practice standards” and the “ supervision and evaluation” of defense attorneys “against such practice standards.”

Conclusion

As concluded in our companion piece, the provision of Sixth Amendment indigent defense services is a state obligation through the Fourteenth Amendment. Although the U.S. Supreme Court has never directly considered whether it is unconstitutional for a state to delegate this constitutional responsibility to its counties and cities, if a state does delegate the responsibility to its local governments, the state must guarantee that local governments are not only capable of providing adequate representation but that they are in fact doing so. A number of states still today rely in all or in part on county funding/administration of indigent defense services with no state oversight as to whether the right to counsel is adequate – including Arizona, California, Illinois, Indiana (misdemeanors, certain felony courts), Kansas (misdemeanors, delinquencies), Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey (misdemeanors), New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Washington.

Much of this blog post comes from the methodology section of our report on trial level right to counsel services in Indiana (publication date: October 18, 2016). The Sixth Amendment Center (6AC) thanks the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) for commissioning that report as a part of its public defense reform program. NACDL acknowledges the support of Koch Industries, whose generous funding helps to support NACDL’s public defense work. That work is also supported by the Foundation for Criminal Justice (FCJ).