Calm down; the New Mexico Supreme Court did not say flat-fee contracts are always constitutional

Pleading the Sixth: Though press reports are generally touting a recent New Mexico Supreme Court opinion as declaring flat fee contracting to be constitutional, the reality is more nuanced. The 6AC walks the reader through the historical background for the decision and analyzes what the opinion really means.

On June 2, 2016, the New Mexico Supreme Court handed down an opinion in Kerr v. Parsons that led some press outlets to declare the Court had ruled indigent defense flat fee contracting to be constitutional. In fact the opinion simply vacated a lower court’s opinion that held flat-fee contracts “contravened the right to counsel” and directed contract attorneys to be paid “no less than $85 per hour.” The Court ruled only that the lower court overstepped its authority by taking the facts from an individual case and applying them universally to all indigent defense contracts. To the Court, the record in the particular case before them did not justify such sweeping action.

However, the Court warned that “future cases,” “presenting other record facts,” could require the Court to decide whether flat fee contracts systemically interfere with an individual’s right to effective representation. Indeed, one justice warned in a concurrence that a system that effectively protects constitutional rights comes at a “substantial fiscal cost.”

Let’s take a look at some of New Mexico’s recent history regarding public defender pay to help sort this all out.

Flat fee contracting in New Mexico

Since 1973, indigent defense services in New Mexico have been state-funded and state-administered. In 2012, the citizenry of the state passed a constitutional amendment requiring that public defense services be moved out of the executive branch and placed in the judicial branch under the direction of an independent commission to prevent undue political interference. The 11-member Commission overseeing the Law Offices of the Public Defender (LOPD) was legislatively created the following year.

New Mexico provides representation through a combination of public and private attorneys. LOPD, with over 220 full-time staff attorneys providing services in 13 of the state’s 33 counties, as well as centralized appellate, post-conviction, juvenile, and training units, is the state’s largest law firm. But trial representation in 20 counties, along with all conflict services statewide, are provided through approximately 160 private attorneys under contract with LOPD.

LOPD’s Chief Defender is statutorily required to “formulate a fee schedule for attorneys who are not employees of the department who serve as counsel for indigent persons under the Public Defender Act.” Historically, the LOPD has paid contract counsel on a per case basis by case severity: misdemeanor ($180); juvenile ($250); 4th degree felony ($540); 3rd degree felony ($595); 2nd degree felony ($650); and 1st degree felony ($700).

Though readers of this blog are perhaps more familiar with flat fee contracts that pay a single lump sum for an unlimited number of cases per year (the predominant type of contract in Utah), contracts that pay a flat fee per case can be even more detrimental to the indigent accused. While an attorney getting paid an annual flat rate certainly has a monetary self-interest to dispose of cases as quickly as possible, that same attorney also has an interest in being appointed to as few cases as possible. But a flat rate per case attorney has a financial self-interest to both dispose of cases quickly and contemporaneously seek appointment in as many cases as possible.

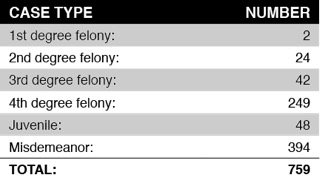

The contract attorney at the heart of Kerr v. Parsons serves as a prime illustration, as detailed in the trial court’s September 2014 minute order. The lawyer practices in Lincoln County, and in 2013, he was assigned the following cases in that county:

For handling 759 cases, LOPD paid the attorney $260,975.00. This attorney also has a contract to handle conflict of interest cases in neighboring Otero County. (To see how this measures up to national standards, click here.)

LOPD Funding

The year 2014 marked the first time that the newly independent LOPD commission presented a budget request to the legislature. In it, LOPD noted that the historical underfunding of the organization (resulting from years of political interference by previous Governors) created a system where “indigent clients are not served as they should be.” Contract attorneys are “abysmally underpaid” creating “a ‘meet and plead’ system where an attorney meets his client and pleads him guilty to a charge on the same day.”

The resulting system was inconsistent with the commission’s recently adopted performance standards. Consequently, the commission voted to ban flat fee contracting in favor of hourly rates “to ensure ethical representation, maintain accountability for funding, pay fairly for work done and to provide incentive to work for the benefit of the client.” LOPD requested funding of $96,431,900 from the legislature (nearly $34 million over the previous budget to cover the hourly rates).

The legislature responded with approximately $12.8 million in new dollars, but it also enacted new statutory language directing that “[t]he appropriations to the public defender department shall not be used to pay hourly reimbursement rates to contract attorneys.”

State v. Carrillo

In 2012, Santiago Carrillo was charged with voyeurism, possession of controlled substances, and drug paraphernalia. He hired private counsel but was unable to pay him, resulting in a motion by his private lawyer to withdraw in 2014. A few months later, Carrillo was accused of a 3rd degree sex crime. The Lincoln County contract lawyer was appointed to represent Carrillo in both cases. That attorney filed a motion on Carrillo’s behalf, requesting the trial court “to compel the State to provide sufficient funds to his contract counsel so that his attorney could provide effective assistance” and to stay the prosecutions until the State provided said funding.

In December 2014, the lower court issued an interim order requiring the LOPD to pay the attorney $85 per hour – not just for Carrillo’s cases, but for all indigent defense cases in Lincoln County. LOPD almost immediately requested reconsideration and asked the court to stay its order during reconsideration, noting that implementation would compromise effective representation in the rest of the state. It was during this time that the legislature passed the budget increase, contingent on LOPD not using its new monies to pay hourly rates. Carrillo subsequently asked the lower court to find that the legislative action violated his right to counsel.

In June 2015, the trial court issued several orders that: a) nullified the statutory ban on paying hourly rates; b) ordered LOPD to pay $85 per hour on all contract cases and for the State to fund LOPD to meet that directive; and, c) stayed the prosecutions of Carrillo while ordering his release from pre-trial detention. Within weeks, LOPD petitioned the New Mexico Supreme Court and asked it to vacate the trial court’s second order (point “b” above).

Back to Kerr v. Parsons

The recent New Mexico Supreme Court order agrees that, under United States v. Cronic, if certain systemic factors are present (or necessary protections are lacking) at the outset of a case, then a court should presume that ineffective assistance of counsel will occur. Hallmarks of a structurally sound indigent defense system under Cronic include the early appointment of qualified and trained attorneys with sufficient time and resources to provide competent representation under independent supervision. The absence of any of these factors can show that a system is presumptively providing ineffective assistance of counsel.

As the New Mexico Supreme Court notes, it has previously found a flat fee contract to violate Cronic once before in the case of State v. Young. But that case was extremely complex, death penalty litigation. In Young, the Court found simply that the attorney in that case would be presumptively ineffective if working under the flat fee arrangement, but it did not presume that a flat fee would necessarily produce ineffective representation in all New Mexico capital cases. The correct judicial approach, therefore, would be to determine whether the flat fee arrangement would presumptively cause the lawyer to be ineffective in that – and only that – specific case. No evidence was presented on other cases involving contract counsel, so the lower court was wrong to presume ineffectiveness in all flat fee arrangements.

The New Mexico Supreme Court was careful to note that their refusal to depart from Young “does not etch into stone the fees currently paid to indigent defense contract counsel.” The Court also noted that the LOPD still has the statutory discretion to establish compensation schedules and can, for example, still set higher flat rate caps without going against the legislative ban on hourly rates. “Moreover, the Legislature’s condition that appropriations for contract counsel not be used to pay hourly rates is not itself constitutionally fixed; it may yet be resolved by the normal democratic process.”

The concurrence

The concurrence in the case goes further – highlighting ways in which the Court could appropriately review the “chronic problem” plaguing the criminal justice system in New Mexico – namely the failure of the state “to provide sufficient funds to pay for effective assistance of counsel for indigent defendants in criminal cases.” The justice specifically cited successful systemic challenges for fair attorney compensation and attacks on flat fee systems are specifically cited.

A glimpse at some of these cases shows that the proposed $85 per hour rate in New Mexico is reasonable:

- Kansas: In 1987, the Kansas Supreme Court determined in State Ex Rel Stephen v. Smith that the State has an “obligation to pay appointed counsel such sums as will fairly compensate the attorney, not at the top rate an attorney might charge, but at a rate which is not confiscatory, considering overhead and expenses.” Testimony showed that the average overhead rate of attorneys in Kansas in 1987 was $30 per hour. Kansas now compensates public defense attorneys at $80 per hour.

- Alaska: “We thus conclude that requiring an attorney to represent an indigent criminal defendant for only nominal compensation unfairly burdens the attorney by disproportionately placing the cost of a program intended to benefit the public upon the attorney rather than upon the citizenry as a whole.” So stated the Alaska Supreme Court in 1987 in DeLisio v. Alaska Superior Court, determining that Alaska’s constitution “does not permit the state to deny reasonable compensation to an attorney who is appointed to assist the state in discharging its constitutional burden,” because doing so would be taking “private property for a public purpose without just compensation.” Importantly – and unlike the Kansas Court before them – the Alaska Court determined that appointed cases did not simply merit a reasonable fee and overhead, but rather the fair market rate of an average private case. Assigned counsel in Alaska are currently compensated rate at rates between $65 and $100 per hour.

- New York: Announcing in the 2003 case, N.Y. County Lawyer’s Ass’n v. State, that “[e]qual access to justice should not be a ceremonial platitude, but a perpetual pledge vigilantly guarded,” the Supreme Court for the County of New York ordered the City and State to compensate assigned counsel attorneys at $90 per hour – a significant increase from the $40-per-hour rate they were being paid. The Court determined that the $40-per-hour rate paid to panel attorneys was “insufficient to cover even normal hourly overhead expenses,” which the Court estimated to be approximately $35 per hour. Deriding the “pusillanimous posturing and procrastination of the executive and legislative branches” for failing to raise the rate for more than 17 years, the Court determined that the other two branches of government created an assigned counsel “crisis” that impairs the “judiciary’s ability to function.” The low compensation was found to result “in denial of counsel, delay in the appointment of counsel, and less than meaningful and effective legal representation.” The following year, the rate was statutorily amended to $75 per hour.

- Washington: “The notes of freedom and liberty that emerged from Gideon’s trumpet a half a century ago cannot survive if that trumpet is muted and dented by harsh fiscal measures that reduce the promise to a hollow shell of a hallowed right.” Thus concluded U.S. District Judge Robert Lasnik in the 2013 case, Wilbur v. City of Mount Vernon. The court’s decision granted injunctive relief against the Washington cities of Mount Vernon and Burlington for “regularly and systematically” providing deficient right to counsel services to the indigent accused. Announcing that “adversarial testing of the government’s case” was so infrequent as to be a “non-factor in the functioning of the Cities’ criminal justice system,” the judge of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington (Seattle) found the appointment of counsel in Mount Vernon and Burlington to be “little more than a formality,” resulting in plea bargains having almost nothing to do with the individualized nature of each case. Importantly, the court found the cities culpable because this lack of adversarial testing of the prosecution’s cases was “natural, foreseeable, and expected,” given the deficient structure of indigent defense services. Flat fees are now prohibited in Washington state.

Conclusion

In just the past two years, three states have banned flat fee contracts for public defense attorneys:

- Idaho: County commissioners may provide representation by contracting with a defense attorney “provided that the terms of the contract shall not include any pricing structure that charges or pays a single fixed fee for the services and expenses of the attorney.” Idaho Code 19-859 (2015)).

- Michigan: The Michigan Indigent Defense Commission is statutorily barred from approving local indigent defense plans that provide “[e]conomic disincentives or incentives that impair defense counsel’s ability to provide effective representation.” Comp. Laws § 780-991(2)(b) (2016).

- Nevada: Announcing that the “competent representation of indigents is vital to our system of justice,” the Nevada Supreme Court banned the use of flat fee contracts that fail to provide for the costs of investigation and expert witnesses and required that contracts must allow for extra fees in extraordinary cases. Order, In re Review of Issues Concerning Representation of Indigent Defendants in Criminal and Juvenile Delinquency Cases, ADKT No. 411 (Nev. filed July 23, 2015).

The contracts currently used in New Mexico counties cause conflicts of interest between the indigent defense attorney’s financial self-interest and the legal interests of the indigent defendant. Whether it occurs through a systemic class action challenge or through the “normal democratic process” of a legislative initiative, New Mexico should follow the lead of these and other states that have banned flat fee practices.