The “Indiana Model” for providing right to counsel services does not work

Pleading the Sixth: On October 24, 2016, the Sixth Amendment Center released its report on trial level indigent defense services in Indiana. Beginning in the 1990s, the “Indiana Model” was widely promoted as potentially the best way to improve the provision of the right to counsel in states throughout America. This new report details the first statewide evaluation conducted of the Indiana Model since its launch in 1989 and shows how and why the system is deficient, resulting in the actual and constructive denial of counsel to the indigent accused in courts all across the state. The main problem is that the model legitimizes and institutionalizes the choice of counties to not meet the constitutional parameters of effective representation. (In a companion piece, we explain how this report serves as a cautionary tale to other states that have adopted approaches to providing defender services similar to that of Indiana – e.g., Georgia, Ohio, New York, Texas, and Washington.)

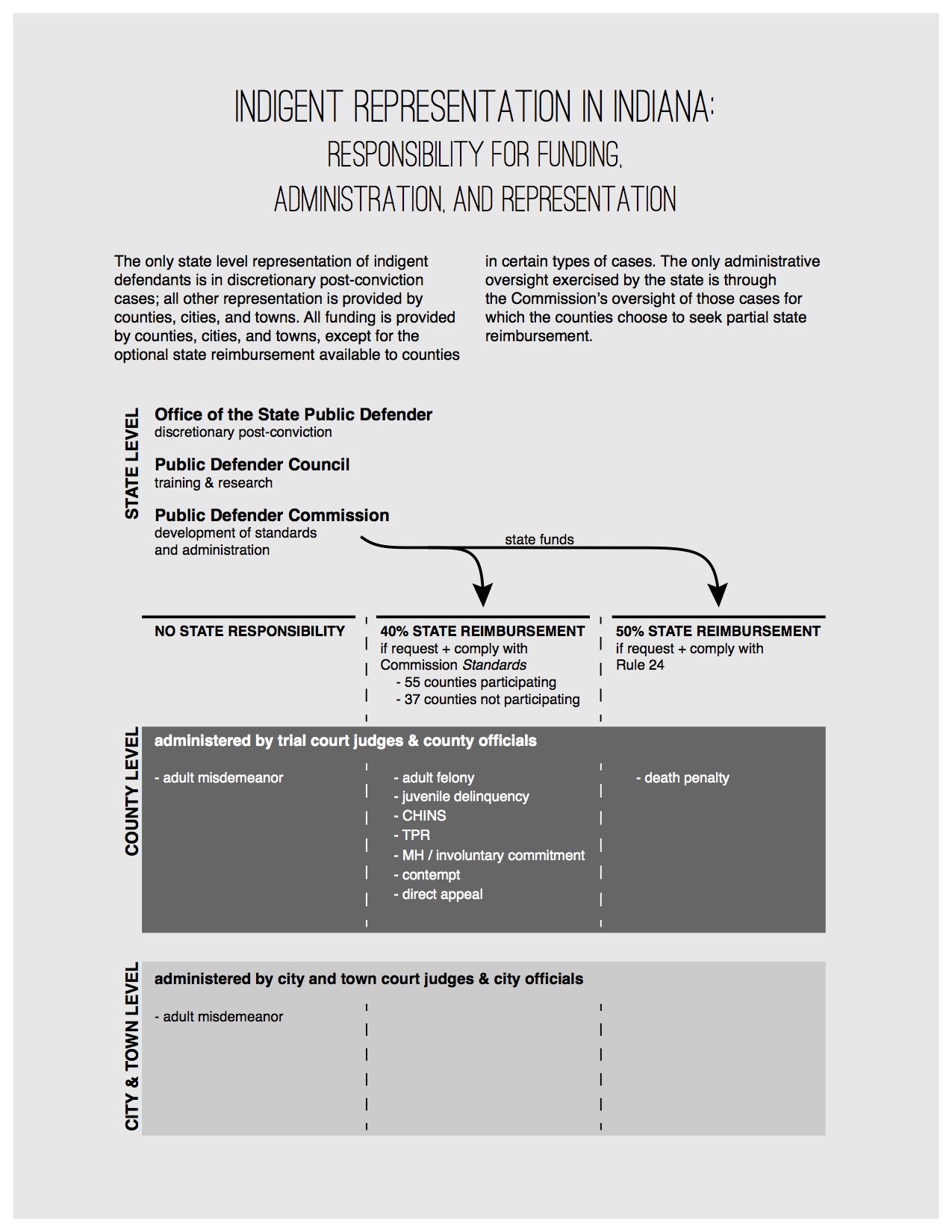

The model Indiana created to provide for the constitutional right to counsel simply does not work. Under U.S. Supreme Court case law, the provision of Sixth Amendment indigent defense services is a state obligation through the Fourteenth Amendment. Although the Court has never directly considered whether it is unconstitutional for a state to delegate this constitutional responsibility to its counties and cities, if a state does delegate the responsibility to its local governments, the state must guarantee that local governments are not only capable of providing adequate representation, but that they are in fact doing so. The state of Indiana, though, has little to no oversight over the majority of indigent defense cases occurring in courtrooms across the state, as explained fully in the Sixth Amendment Center (6AC) report, The Right to Counsel in Indiana: An Assessment of Trial Level Indigent Defense Services, released October 24, 2016. (Read 6AC press release.)

Of course, the lack of state oversight of indigent defense services is not by itself outcome-determinative. That is, the absence of institutionalized statewide oversight does not of necessity mean that all right to counsel services provided by all county and municipal governments are constitutionally inadequate. But it does mean that, prior to the 6AC report, Indiana had no idea whether its Fourteenth Amendment obligation to provide competent Sixth Amendment services was being fulfilled in all of the courts in its counties and cities. The 6AC conducted courtroom observations, interviewed criminal justice stakeholders, and collected and reviewed data in eight representative Indiana counties and from the state’s three state-level agencies related to the provision of indigent defense. The study was performed on behalf of a statewide Indiana advisory group that included representatives from the Indiana Supreme Court, both chambers of the Indiana legislature, the state bar association, the Indiana Public Defender Commission, the Indiana Public Defender Council, the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council, the judges’ association, the Indiana Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and the Association of Indiana Counties.

The 6AC determined that the state of Indiana’s constitutional obligation to provide counsel at all critical stages of a criminal proceeding is not consistently met at the local level. Rather, some courts encourage defendants to negotiate directly with prosecutors before being appointed counsel, others accept uncounselled pleas at initial hearings, and many courts use non-uniform indigency standards to deny counsel to defendants who would otherwise qualify for counsel in a neighboring county. Indiana does not consistently require indigent defense attorneys to have specific qualifications necessary to handle cases of varying severity or to have the training needed to handle specific types of cases (other than for capital cases). The public defense systems in many Indiana counties have undue judicial interference, undue political interference, flat-fee contracts, or all three, that produce conflicts between the lawyer’s self-interest and the defendant’s right to effective representation. These conflicts result in public defense attorneys throughout Indiana carrying excessive caseloads and spending insufficient time on their appointed cases.

Let us sort this all out for you.

The “Indiana Model”

In Indiana, counties and cities are responsible for funding and administering all indigent defense services. Indiana counties (but not cities) may, if they so choose, receive a partial reimbursement from the state for their indigent defense costs – excluding misdemeanors, for which the state provides no reimbursement at all — in exchange for meeting standards set by the Indiana Public Defender Commission (IPDC). However, counties are also free to forgo state money and avoid state oversight. What many Indiana counties have realized is that they can contract with private attorneys to provide indigent defense on a flat fee basis for an unlimited number of cases for less money than it would cost to comply with state standards (even factoring in the state reimbursement). Thirty-seven of Indiana’s 92 counties (40%) choose not to participate in the state’s reimbursement program as of June 30, 2015, more than 20 years after the state reimbursement program began. This hybrid system for right to counsel services, known as the “Indiana Model,” where lawyers for some indigent defendants are required to meet standards conducive to constitutional effectiveness while lawyers for other defendants are not, both institutionalizes and legitimizes counties’ choices to not fulfill the minimum parameters of effective representation required by the U.S. and Indiana constitutions.

The state of Indiana has no mechanism to ensure that its constitutional obligation to provide effective counsel to the indigent accused is met:

- in misdemeanor cases in any of its courts;

- in felony and juvenile delinquency cases, at trial and on appeal, in counties and courts that do not participate in the state reimbursement program; and

- in those capital cases for which counties do not seek state reimbursement.

Even in those counties that do participate in the state reimbursement programs and are subject to the IPDC standards, Indiana has only limited capacity to ensure that its constitutional obligations are met.

Misdemeanors matter. Although a misdemeanor conviction carries less incarceration time than a felony, the collateral consequences can be just as severe. Going to jail for even a few days may result in a person losing professional licenses, being excluded from public housing and student loan eligibility, or even being deported. For most people, misdemeanor courts are the place they will have their initial, and hopefully only, contact with the criminal justice system, yet Indiana has no mechanism at all to ensure that indigent misdemeanor defendants receive effective assistance of counsel. The state of Indiana does not provide any funding at all for the provision of misdemeanor representation to the indigent, and courts and public defense attorneys do not have to abide by the IPDC standards in providing representation in misdemeanors.

Nearly one-third of Indiana’s people live in one of the thirty-seven counties that, as of June 30, 2015, do not participate in the state’s reimbursement program. In addition, the Lake County juvenile and county division courts do not participate. For indigent defendants charged with felonies or juvenile delinquency in these counties and courts, Indiana has no mechanism to ensure that its constitutional obligation to provide them with effective representation is met at trial or on direct appeal. The IPDC has no authority whatsoever over the representation of indigent people in these courts, and the courts and public defense attorneys do not have to abide by the IPDC’s standards nor report to the IPDC on their indigent defense representation. In other words, one out of every three indigent people in Indiana runs the risk of receiving counsel whom the state cannot ensure will provide effective representation.

Ostensibly, Indiana has in place a mechanism to provide effective oversight of indigent defense services in most of the courts in the 55 counties that, as of June 30, 2015, do seek reimbursement from the state and therefore in theory comply with the standards set by the IPDC. Further, Indiana’s reimbursement program is open to all of the state’s 92 counties for everything except misdemeanors. Yet, two things have hindered the effectiveness of that program. First, state funding for reimbursements to the participating counties has not always kept pace with the expressed goal of reimbursing 40% of indigent defense costs other than for misdemeanors. For example, reimbursements to counties for non-capital representation dropped to a low of 18.3% in 2006. The unreliability of reimbursements has been at least the partial cause of a number of counties leaving the program and the decisions by other counties not to participate to begin with. Second, for most of its history, the IPDC operated with only a single full-time staff member to oversee compliance with the organization’s standards in the participating counties and courts. In 2014, a second full-time staff position was added. The state is obligated to ensure effective representation to the indigent accused facing a potential loss of liberty in all of its five appellate districts, 91 circuit courts, 177 superior courts, and 67 city and town courts. No two people, no matter how talented, could ever possibly ensure compliance with standards in so many jurisdictions.

Worse yet, because the state of Indiana does not require that all counties and courts meet minimum standards, even those counties that do participate in the state reimbursement program and subject themselves to oversight by and compliance with the IPDC are free to walk away from standards and oversight at any time. Eight counties have voluntarily left the reimbursement program, most often after the IPDC determined that their public defense systems were not meeting standards, and another 29 counties have chosen never to participate at all. These are often the counties most in need of state help to provide effective assistance of counsel to the poor.

Explaining why the “Indiana Model” does not work: the Scott County example

The jurisdictions that are often most in need of indigent defense services are the ones that are typically least likely to be able to afford them. Indiana requires its local governments to fund indigent defense services in the first instance. However, Indiana counties have significant revenue-raising restrictions placed on them by the state, while being statutorily prohibited from deficit spending. The primary source of revenue available to local government is property taxes, but even there the amounts local governments are allowed to assess are stringently limited by the state. Worse yet, factors that in many instances lead to higher crime rates — low property values, high unemployment, high poverty rates, limited household incomes, limited higher education, etc. — are often the exact same factors that limit counties’ revenues. And those same counties often have a greater need for broader social services, such as unemployment or housing assistance, meaning the amount of money that could be dedicated to upholding the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution is further depleted.

Scott County, for example, is one of the poorest counties in Indiana. Property values are low, and it is geographically small, so there is less land to assess for property taxes. The 6AC site visit to Scott County coincided with the outbreak of an HIV epidemic. As one judge stated: “If you look at Austin – that community is imploding on itself.” The small community had confirmed 20% of its population as being HIV+, and the number continued to climb as testing spread further. But the judge noted that the HIV crisis is just the latest in a long line of issues the county has faced. In the late 1980s, it was cocaine. In the 1990s, it was pills. Just as the county fought and won each successive battle, the judge is convinced it will win out over the HIV scare as well. But it is taking the few resources the county has available to do it. There is nothing left for criminal justice – and certainly not enough to adequately fund the right to counsel within Scott County.

Rather than spending more on public defense in order to meet IPDC standards, Scott County left the state reimbursement system and reduced the number of its public defense attorneys from ten to six. The county uses flat fee contracts that pay each attorney a single fee to handle an unlimited number of cases. There is no line item available to pay for investigators or social workers, so none of the attorneys ask for these support resources on their indigent clients’ cases. When asked what is needed to remedy the situation, the judge said: “The state needs to take over the public defender system.”

Cronic violations in Indiana – the actual and constructive denial of counsel

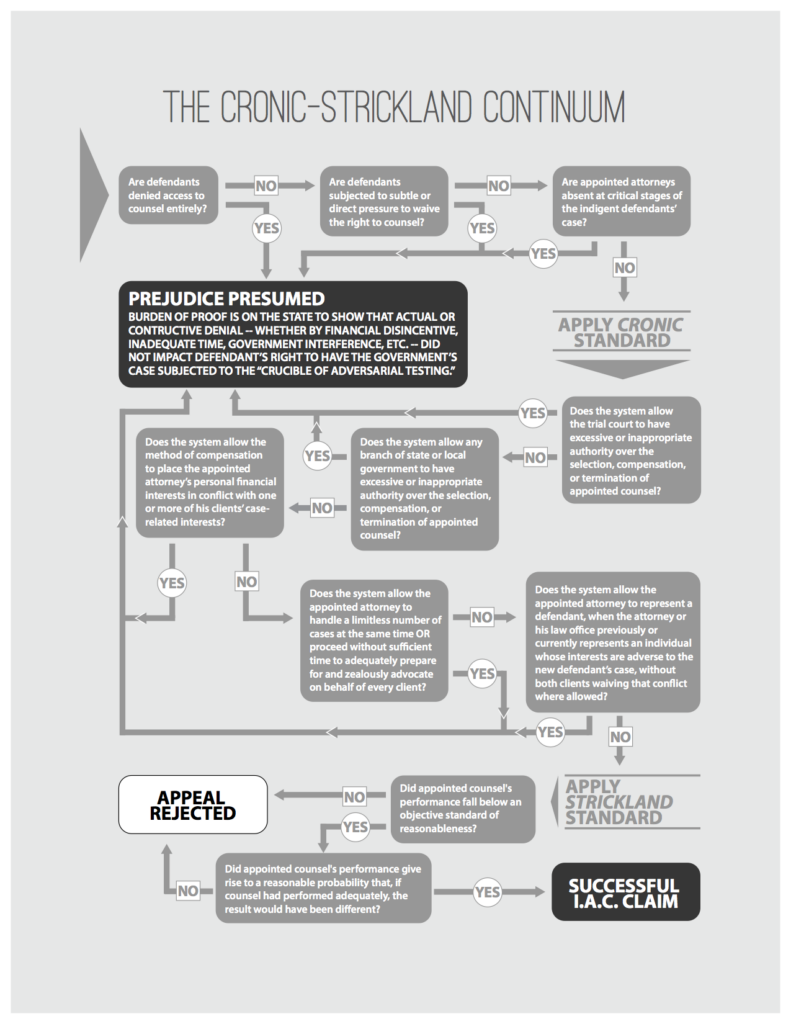

In United States v. Cronic, 466 U.S. 648 (1984), the U.S. Supreme Court determined that, if certain factors are present (or necessary factors are absent) in an indigent defense system, then at the outset of any case a court should presume that ineffective assistance of counsel will occur. Hallmarks of a structurally sound indigent defense system under Cronic include the early appointment of qualified and trained attorneys with sufficient time and resources to provide competent representation under independent supervision. The absence of any of these factors indicates that a system is presumptively providing ineffective assistance of counsel.

Throughout Indiana, the 6AC found a number of systemic factors that contribute to the constructive denial of counsel under Cronic. Lawrence County’s history exemplifies this finding. In 2010, Lawrence County was mired in a public defense crisis. Four private defense lawyers who had been providing services in an unlimited number of cases for a single flat fee decided they could no longer provide effective representation under such a financial arrangement. Each moved to decline new appointments. The county turned to the IPDC for assistance and decided to form a county public defender office.

The first chief defender of the office realized early on that public defenders in Lawrence County historically had not attended initial hearings, and many cases were resolved at those initial hearings by prosecutors entering into plea deals with uncounselled defendants, in direct violation of Sixth Amendment case law. Lawrence County was caught in a quandary. The defender office needed to either: a) exceed IPDC caseload standards to begin providing representation at initial hearings (thus risking the loss of state reimbursement); b) increase the number of staff attorneys (thereby increasing the county’s public defense cost); or c) turn a blind eye to a blatant constitutional violation.

Fearing that a new budget battle might jeopardize the existence of the entire public defender office, the chief public defender came up with a half-measure. The office began staffing all initial hearings, but only as a “friend of the court” to answer questions a defendant might have about the prosecutor’s plea offer. By not being formally appointed to the cases, the office does not have to report the workload to the IPDC (even though the office’s attorneys spend significant hours at initial hearings), giving the appearance that the office complies with IPDC caseload standards when it does not. The county continues to receive reimbursement from the IPDC, and the county does not incur the increased cost of hiring more attorneys to handle the greater caseload, as it would be required to do if the cases were reported.

The problem is that the defendants at these initial hearings think they have a lawyer representing them, when in fact they do not. The lawyer is not securing discovery from the state, interviewing witnesses, examining evidence, reviewing statutes, or negotiating directly with the prosecutor on behalf of the defendant – all of the things lawyers must do to determine the quality of a plea offer. This is the very definition of “providing an attorney in name only” that triggers what Cronic calls a “constructive denial of counsel.”

In other counties, the nationally familiar issue of excessive public defender workloads comes into play. The estimated number of cases assigned to each Elkhart County public defender office attorney in 2014, applying the IPDC’s Standards for attorneys who lack adequate support staff, are startlingly high – in some instances more than 5 times the maximum allowed for an attorney in a year. In the Lake County county division courts, attorneys who devote approximately only 20% of their professional hours to indigent clients are carrying caseloads far in excess of that allowed under any possible measure for a full-time attorney. In 2014, one Marion County attorney handled 1,333 misdemeanor cases in a single 12-month period. This is more than three times the maximum annual caseload allowed for misdemeanors under national standards.

Conclusion: Moving forward

At the 6AC, we believe that there is no one-size-fits-all model that all jurisdictions must use to deliver effective defense services. That is, each jurisdiction must take into account its unique court structures and cultures, geographic expanse and population centers, and criminal procedures and court rules, to create a system that works best for the citizenry of each state. In designing its indigent defense system, what every state must do – the one thing that is not optional – is to comply with the requirements of current Sixth Amendment case law and prevailing national standards (most notably, the American Bar Association’s Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System).

The 6AC suggested broad recommendations for Indiana, and now it is for Indiana criminal justice stakeholders and policymakers to come together and form consensus on how best to move forward for the people and courts of Indiana (as was done most recently in Michigan, Utah, and Idaho). We list the recommendations – generalized to all states – to demonstrate what needs to be done to stem the denial of counsel:

- All states must require all courts in all counties to meet the parameters of effective indigent defense systems as defined in United States v. Cronic. At a minimum, binding standards must be promulgated and applicable at trial and on direct appeal for all adult criminal and juvenile delinquency cases, including conflict cases, related to: a) presence of counsel at all critical stages of a criminal proceeding; b) indigency determinations; c) attorney performance; d) attorney qualifications, training, and supervision; and, e) attorney workloads.

- All states must ensure a comprehensive and mandatory training and supervision system for all indigent defense providers based on the above standards.

- All states must create an independent system to evaluate compliance with, and enforce adherence to, all standards (capital and non-capital).

- All states must prohibit contracts that create financial disincentives for attorneys to provide effective representation.

- All states should create a statewide appellate defender office as a check against inadequate trial level representation.

Learn more in our companion piece about how this report serves as a cautionary tale to other states that have adopted approaches to providing defender services similar to that of Indiana – e.g., Georgia, Ohio, New York, Texas, and Washington.

The Sixth Amendment Center (6AC) thanks the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) for commissioning this report as a part of its public defense reform program. NACDL acknowledges the support of Koch Industries, whose generous funding helps to support NACDL’s public defense work. That work is also supported by the Foundation for Criminal Justice (FCJ).