The State of the Nation on Gideon’s 60th Anniversary

Pleading the Sixth: The fear of government unduly taking away one’s liberty led the United States Supreme Court to unanimously declare it an “obvious truth” that no indigent person can be assured a fair trial against the “machinery” of law enforcement without a lawyer. “The right of one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental and essential to fair trials in some countries,” the Court announced on March 18, 1963 in Gideon v. Wainwright, “but it is in ours.” Sixty years later, 6AC reflects on where the nation stands in fulfilling Gideon’s promise.

In honor of Gideon’s 60th anniversary, 6AC surveyed all state and local governments to estimate total national expenditures on the right to counsel under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. We estimate that, collectively, state and local governments spend approximately $6.5 billion, or $19.82 per capita, on indigent defense. Compared to the $123 billion the nation spends on police and the $82 billion on corrections, this is a drop in the bucket.

Of serious concern, though, are states that spend far less than $19.82 per capita:

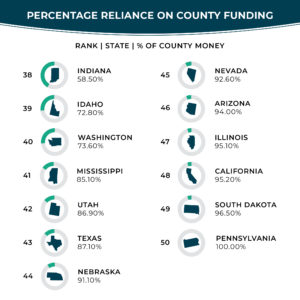

And states that have punted a significant responsibility for indigent defense funding to local governments.

Still, we should not overlook the fact that this is a significant increase from the estimated $2.3 billion the nation spent on indigent defense near the time of Gideon’s 50th anniversary. This begs the question: where has some of the increase in dollars gone over the past decade?

We have good news worth celebrating.

More State Oversight

State government, not local government, is responsible for ensuring that every indigent defendant charged with a jailable offense is provided with a constitutionally effective lawyer. This obligation always rests with the state, even when a state delegates its right to counsel responsibilities to local governments. To fulfill its constitutional duty, the state must have a state-level entity that has the authority and ability to evaluate whether local indigent defense systems can, and in fact do, meet constitutional muster.

At the time of Gideon’s 50th anniversary, Michigan had no state oversight of trial-level indigent defense services. After a Governor’s advisory commission concluded that the state’s indigent defense system was an “uncoordinated, 83-county patchwork quilt,” Michigan passed a comprehensive legislative package in 2013 creating the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission (MIDC). MIDC has the power to develop, monitor, and enforce standards statewide. Both state and local governments pay to implement these standards. Over the past decade, Michigan has been – brick by brick, standard by standard – building a system designed to protect the right to counsel for indigent defendants across the state.

Other states that created a state oversight entity include:

- New Mexico amended the Public Defender Act to create an independent commission that meets national standards. (2013)

- Idaho established the Idaho Public Defense Commission, which creates and enforces statewide standards such as workload controls. (2014, 2016)

- Delaware established the Office of Defense Services, which has statewide oversight of primary and conflict indigent defense services. (2015)

- Utah established the Utah Indigent Defense Commission, which creates and enforces statewide standards. After witnessing benefits in adult representation, the state legislature expanded and set quality standards for juvenile representation. (2018)

- Nevada established the Board of Indigent Defense Services, which creates and enforces standards such as workload controls and bans on flat fee contracting. (2019)

Several states expanded their oversight capabilities:

- New York’s Office of Indigent Legal Services has worked with counties and New York City to create local plans that ensure representation at arraignment, compliance with caseload standards, and quality services through supervision, training, and access to non-legal support such as investigators, mitigation specialists, and experts. (2017)

- Colorado requires all 215 municipal courts to provide counsel in municipal violations that carry jail time. The Office of the Alternate Defense Counsel assists municipalities by approving qualified attorneys or conducting evaluations to ensure the selection of attorneys is merit-based and free from political and judicial interference. (2020)

- Maine reconstituted its state oversight board to meet independence standards (2019); increased the board’s oversight capacity by tripling its staff with a 50% budget increase; and banned flat fee contracts in favor of public defenders (2021) and assigned counsel at a $150/hour compensation rate. (2023)

More State Dollars

National standards call for state funding rather than local or hybrid state-local funding because counties and municipalities most in need of indigent defense services are often the ones least able to afford them. This past decade bore witness to some states relieving their local governments of the burden of funding indigent defense.

- Despite relying on counties to fund a major percentage of funding, the Idaho legislature voted to move to 100% state funding by 2024. (2023)

- Michigan went from 0% to 78% state funding ($130 million annually) for all indigent defense services. (2023)

- New York devotes $273.8 million annually as a result of the 2014 Hurrell-Harring v. New York settlement and its extension to improve indigent defense services. This, coupled with the $47 million per year that the state’s court system devotes to caseload relief for New York City’s indigent defense providers, results in the state contributing $401.8 million annually – a significant increase from the $81 million spent in 2013.

- Ohio, for the first time, reimbursed counties 100% of their indigent defense costs. (2022)

More Coordinated Systems

Governments are not required to employ a particular model for delivering indigent defense services. 6AC has seen the good and bad in nearly every type of model: government-employed public defender offices, government-contracted nonprofits, and various private attorney systems. What matters is that the model a government chooses meets all constitutional requirements. A critical component of this is ensuring that indigent defense lawyers (private and public) are independently supervised and managed effectively.

The past decade saw a rapid increase in coordinated indigent defense systems through the creation of new public defender offices and managed assigned counsel systems.

6AC’s 2019 evaluation of Armstrong County and Potter County, Texas (Amarillo) showed that more than 74% of all misdemeanor defendants had no lawyer. Faced with this evidence, policymakers in both counties completely overhauled their joint system and created a new one. Today, all indigent defense services in Amarillo are overseen by an independent commission (instead of by judges), and the first-ever public defender office and managed assigned counsel system now has lawyers meeting with indigent defendants before the first court appearance.

The Amarillo public defender office is one of 13 new public defender offices serving 38 counties in Texas that opened this past decade. Texas has also been creating new managed assigned counsel systems, including in Bexar County (San Antonio) and Harris County (Houston).

Other newly created public defender offices and managed assigned counsel systems include:

- In Alabama, public defender offices were created in Jefferson County (Birmingham) in 2013 and Montgomery County in 2015.

- After 45 years, Santa Cruz County, California switched from contracting with a private law firm for primary indigent defense services to creating a public defender office that has pay parity with the local prosecutor’s office, and a new managed assigned counsel system for conflict services. (2022)

- With strong state financial support, 32 of Michigan’s 83 counties now have public defender offices, an increase from three in 2013. There are new offices in the two most populous counties: Oakland (Pontiac) and Wayne (Detroit).

- Maine authorized positions for the first-ever government-employed public defenders to cover rural areas. This means there are no states left that fully rely on individual private attorneys to provide indigent defense services. (2022)

- Tennessee created a statewide appellate defender office to provide direct representation in all appeals and to aid trial-level attorneys. (2022)

Where will America be on Gideon’s 70th Anniversary?

The road to realizing Gideon’s promise is long. We highlighted states that took steps over the past decade to improve their systems, but no system is perfect nor immune from reasoned critique.

As a nation, we witness victories when local, state, and federal governments work together to build and reform indigent defense systems. 6AC remains optimistic that more states will come into constitutional compliance. Here are just a few reasons to remain hopeful:

- On March 7, 2023, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro delivered his first state budget address since taking office and stated: “Pennsylvania is one of only two states in the nation that provides zero state dollars for indigent defense. That’s not a list we want to be on. That’s why I am proposing today – for the first time – we make a 10-million-dollar investment in public defenders this year, and every year going forward.”

- On March 6, 2023, the Illinois Supreme Court announced the creation of the Illinois Judicial Conference’s Criminal Indigent Defense Task Force to study how best to build an indigent defense system as a follow-up to 6AC’s report.

- On February 24, 2023, South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem signed into law House Bill 1064 creating a task force to study indigent defense. The need to consider new ways of providing indigent defense services was spearheaded by Chief Justice Steven Jensen and the Task Force will first meet on March 31.

- On January 10, 2023, Iowa Chief Justice Susan Christensen, in her annual Condition of the Judiciary address to the state legislature, called attention to the decreasing numbers of private attorneys willing to handle conflict cases at the statutory rate of $68-$78/hour, resulting in too few lawyers handling too many cases. “Our federal and state constitutional obligation to provide indigent counsel is on the verge of snapping,” Christensen said. “This is a crisis in nearly every rural and urban county in our state.”

- In January 2023, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Guam requested 6AC to study its indigent defense system.